Not a poem today, instead a short, short fiction, about 800 words.

Shirley Jackson (1916-1965), wrote The Lottery, one of the best known short stories in American literature. It created a sensation among readers when it was first published by The New Yorker in 1948, with demands for an explanation and many cancelled subscriptions. My story doesn’t necessarily depend on having read hers, but it is a sort of commentary on or delving into, which necessitates a spoiler alert. You can read The Lottery here first if you wish. We’ll see how my subscriptions fare. :-)

The Oldest Lottery

by alan girling

"Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon." Old Man Warner in The Lottery by Shirley Jackson

It brings to mind the lottery, the one in the village, where every June each one of three hundred villagers was given a slip of folded paper, with one slip marked by a black dot. How this particular year Mrs. Hutchinson unfolded hers, and the stoning ensued. Mrs. Hutchinson left dead amongst the piles of stones.

You may remember it from your high school English, too. How you had to be told what the lottery meant because it seemed so impossible. So alien to the utter normality of your peace-enclosed world. And even then, it was a mystery.

But what you may not remember, because it was never mentioned in high school, were the years that preceded, and the years that followed, how every year was, and has been, the same, the story of the lottery re-cycled, entrenched, like the village’s very own Groundhog Day: Mrs. Hutchinson unfolding her slip, finding again the black dot, and then the inevitable stoning. Poor Mrs. Hutchinson.

Sometimes she would scream helplessly; sometimes she would quietly lie down; other times she would stand defiantly as the stones rained upon her. Often, too, she would catch the stones or pick them up and throw them right back. But no matter the year, or how she would answer the lottery, she always died a miserable death.

She never did, however, get used to the role she had been assigned, the part they wanted her to learn and accept, exactly what made her so useful to them. In that, she was firm, solid as a rock.

*

It began, according to now obscure lore, with the very first village death, the death of the mother of a child at the moment of the child’s birth. And with that, the great fear it engendered that spread amongst the villagers. Every one of them now deeply afraid, and even more, afraid of the fear itself.

So they gathered and considered. How could they control the fear, weaken, eliminate the fear, or at least put it in its place?

They observed, correctly, that the fear could not be excised; it was now a permanent feature of their lives. It did seem possible, however, with a little mental effort, a few politic words, to shift it, move it around, in a way, transfer it, from community to community. Even from person to person.

So, since the village was small, with few resources and situated far from other villages, they decided to move the fear from person to person. And in order to get the greatest benefit for the greatest number of people, they determined that one person would be chosen to take it on, to genuinely experience the fear in all its immanence, one person on behalf of, instead of, the others, one person to whom all the others would bestow the fear they were so afraid of. Annually, permanently, ritually, hopefully.

And that person, they decided, would be Mrs. Hutchinson.

Why her? Why Mrs. Hutchinson, also known as Tessie, a wife, a mother of three, an upstanding member of the community, and not someone else? No reasons were given at the time; indeed, none could be given, none beyond a broad consensus, not in a village where one could say it held a deep belief that every resident was loved and thought to have equal value, each living person born in the image of all that is good and true.

One thing, however, it might be noted, did make Tessie stand out from the others. She baked delicious peach pies that everyone loved, the most delicious in the village, in fact, from a recipe all her own. And she shared her pies freely, at charity bake sales, birthday celebrations, local church dinners. She was admired by all, yes, but also, one cannot deny, envied just a little bit. And if they even thought about it at all, and some may have for a fleeting moment, they would have to admit to feeling it, they just knew, that they would love her pies that much more if she were dead.

*

And still today, every June, the three hundred villagers gather for the lottery; after so many years, each one is fully immunized and armed with arguments honed for centuries, full of falsehoods, sophistry and libellous bile, the original motive lost to time, with Mrs. Hutchinson as its perennial victim. Even going so far as to say it must be her own fault, for how otherwise could the outcome always be the same.

Poor Tessie. Despite all the arguments bearing against her, she cheerfully makes her pies, participates fully in the community as an upstanding villager, wife, and mother to her three children. She does feel keenly, on their behalf, everyone’s fear of life’s catastrophe and hopes against hope that she will not get the black spot this time, even with the almost certain knowledge she will. And yet, against all odds, every year, she lives on, risen and strong, until the next June. She will never, ever, get used to it.

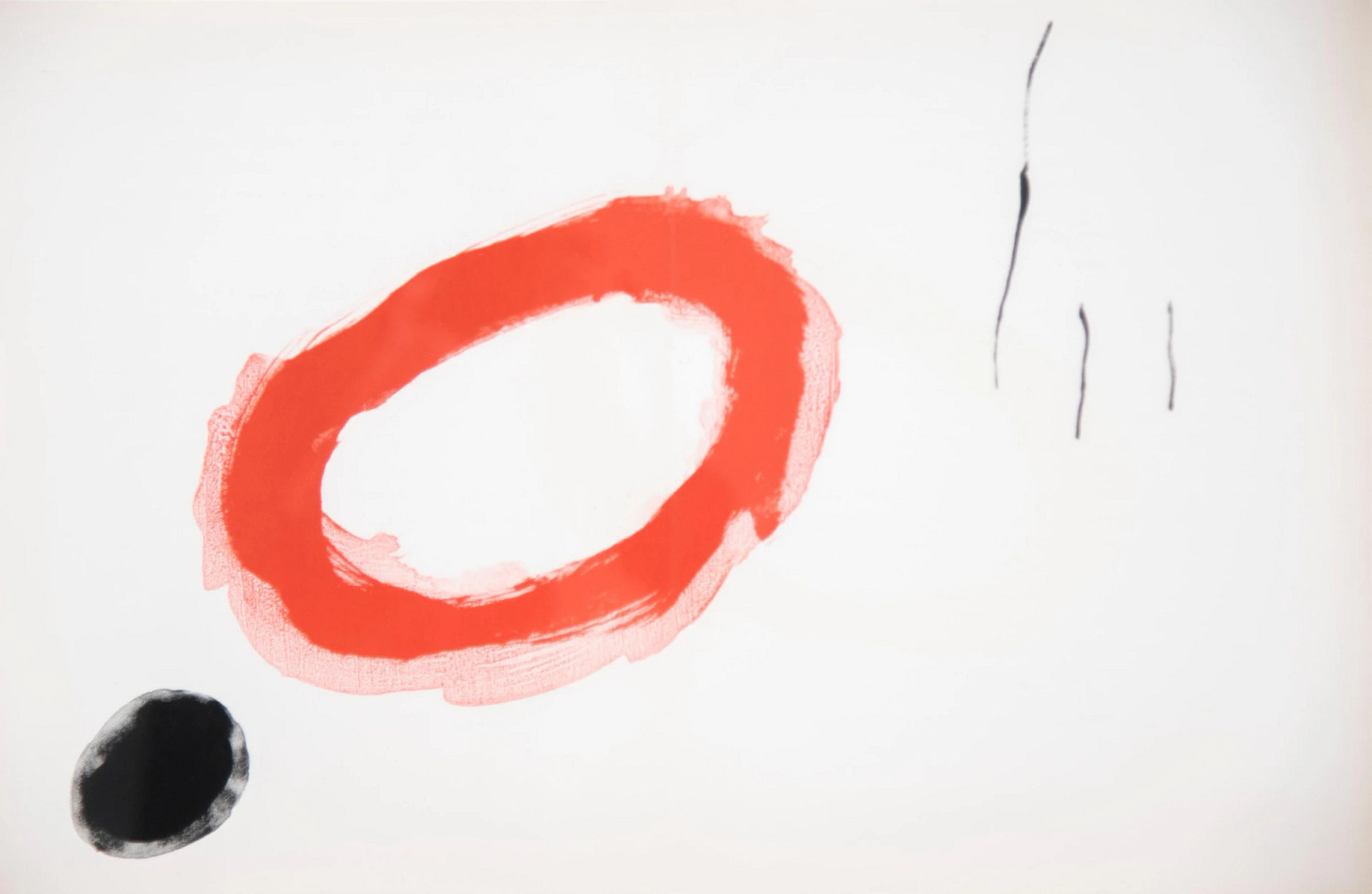

I love how the Miro and your story match so perfectly and awfully, and how your story extends Jackson's. Yikes!

Well done, Alan. I wonder if Rene Girard’s ideas of mimetic desire and ritual scapegoating have ever been applied the “The Lottery.”